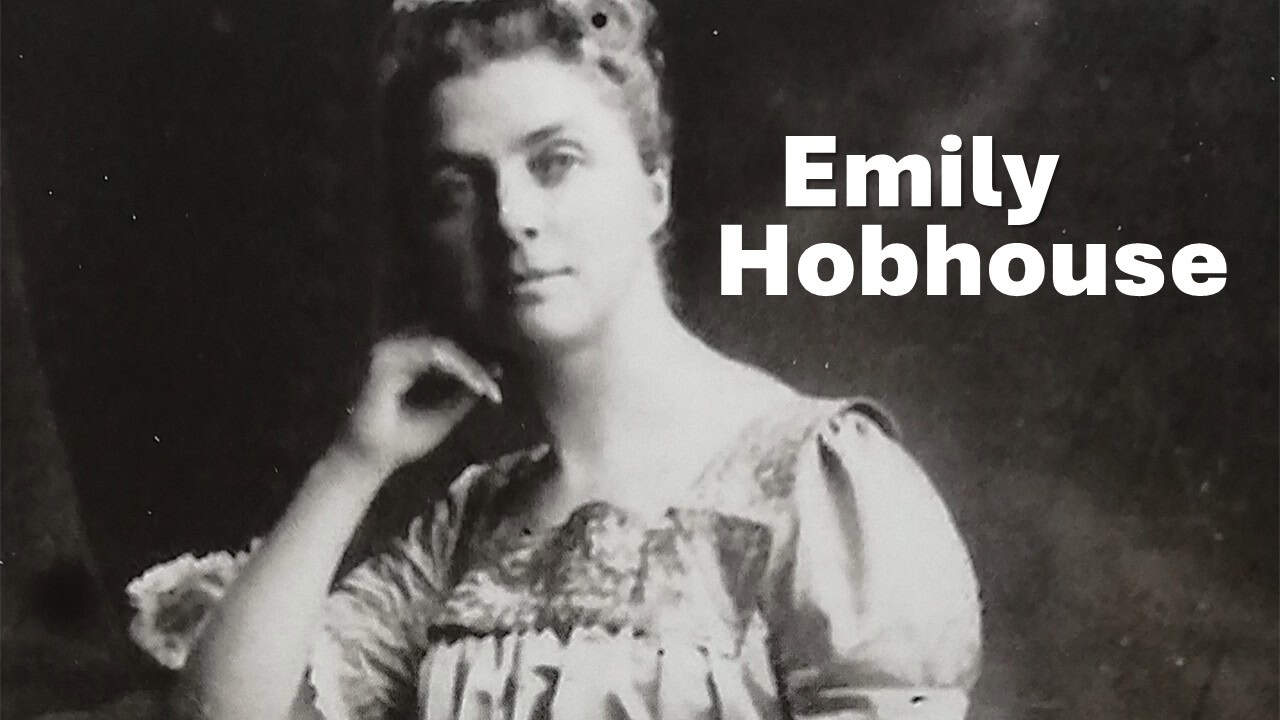

Much has been written about Emily Hobhouse, the “heroine from afar” as author Rykie van Reenen described her. This Englishwoman, who could identify so closely with the plight of the Boer women and children during and after the Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902), played a huge role in alleviating the plight of the victims in British concentration camps and in making the British public aware of the abuses there. She was also the first foreign national to receive a state funeral in the country and to be laid to rest at the Women’s Monument in Bloemfontein.

Although she championed various key issues during her lifetime, she died in relative obscurity, and today few Britons know of her and the role she played in relieving suffering. However, in 2024 a museum was opened in her birthplace that aims to commemorate her inspiring life.

Emily was born on 9 April 1860 in St Ive, Cornwall, England, as the fifth of six children. She was a scholarly child but was educated at home only. Her mother died when she was twenty and she then cared for her ailing father for the next fourteen years. She was clearly a very caring person, because after his death she went to Minnesota in the USA to do welfare work among Cornish miners there. While in the USA she got engaged to John Carr Jackson. They even bought a farm together in Mexico, but the engagement and her investments failed. She returned to England in 1898.

With the outbreak of the Anglo-Boer War in 1899, Leonard Courtney, a British member of parliament for the Liberal Party, invited her to become the secretary of the women’s branch of the South African Conciliation Committee. In 1900 she became aware of the plight of so many Boer women and children as a result of the war and British action against them. She set up a fund, the South African Women and Children Distress Fund, and to oversee its management, she left for the Cape on 7 December 1900. With the help of influential friends and family, she was officially introduced to the British High Commissioner, Lord Alfred Milner. With his help and with the permission of the military commander, Lord Herbert Kitchener, she was able to obtain two railway carriages to transport more than 12 tons of goods to Bloemfontein and the concentration camps.

Emily visited several concentration camps personally and was deeply shocked by the conditions she found there. She compiled a report about it that was published in England and tabled in both houses of parliament. In response, an official commission was sent to inspect the camps. It was headed by Millicent Fawcett and substantiated Emily’s allegations, but without crediting her for bringing the issues to light.

When she returned to the Cape in October 1901, she was denied permission to go ashore. She was deported to England, but refused to leave. Eventually a group of men had to tie her up with her shawl and carry her to the ship that was to take her back to England!

Back home, she was also criticised mercilessly by British supporters of the war. She was called a “traitor” and a “hysterical woman”. She did not let this deter her and wrote a book about her experiences entitled The brunt of the war and where it fell. It was published in 1902.

After the war, she visited southern Africa again – initially to help with reconstruction and in 1908 to set up spinning and weaving schools to uplift Boer women. In 1913, she travelled to the country for the inauguration of the Women’s Monument. Unfortunately, she was unable to attend the latter ceremony due to ill health. Her inaugural address was read on her behalf and focused on equality, forgiveness and warnings against the abuse of power.

She also advocated other important causes in Britain, for example, to obtain voting rights for women and pacifist actions against the First World War. One of her exceptional achievements is that she ensured that thousands of children in war-torn Leipzig received food daily for more than a year. The Boer women whom she had supported in Africa helped her in this endeavour by collecting more than £17 000 under the leadership of President M.T. Steyn’s wife Tibbie.

Emily was well versed in languages and, in addition to English, also knew French, Latin, Spanish, Italian, German and Afrikaans. About the latter she said: “What humour it can convey, what tenderness, what poetic feeling.”

She was very fond of animals. On her visits after the Anglo-Boer War, she was accompanied locally by her cat and a St Bernard pup named Caro. Caro died a few years later due to illness and this broke her heart. She never had a dog again. On two occasions, however, she herself killed snakes that came too close to her – once with a parasol and once with a proper umbrella!

Emily passed away on 9 June 1926 in London. The cause of her death was a combination of heart failure and cancer. To the very end she lived out her favourite motto, “Rather wear out than rust out”. Her ashes were placed in a niche at the foot of the Women’s Monument in Bloemfontein. More than 20 000 people were present at this ceremony in Bloemfontein.

The house museum in St Ive (where she lived from birth to the age of 34 years) invites visitors to explore Emily’s legacy. It also includes exhibitions about life in the village during the Victorian era, as well as on the Anglo-Boer War. An on-site restaurant serves authentic South African cuisine.

The museum describes Emily as a humanitarian, pacifist and feminist who “roared with truth and defiance” in “an era that silenced women”. The museum and accompanying website provide a fitting tribute to this remarkable woman who cared so passionately for the welfare of others.

Also read: Monument to a Boer War hero in the heart of France