Early in August 1999 our family arrived in Milstead, Kent. “This is where we are going to live from now on,” I informed our children. Simon, our youngest, immediately asked carefully: “Are there any lions here, Dad?”. After our vacation in the Kalahari just shortly before our immigration to the UK, he wanted to make sure what to expect, because those huge black-maned lions had made quite an impression on him. On one of the memorable days during that visit to the Kalahari Gemsbok Park (as it was known then), we saw 21 lions. Our wonderful African memories always kept us on the lookout for signs of something wild in “tame” old England and Europe. I remember Simon complaining once that except for rugby, England was actually fairly “boring”.

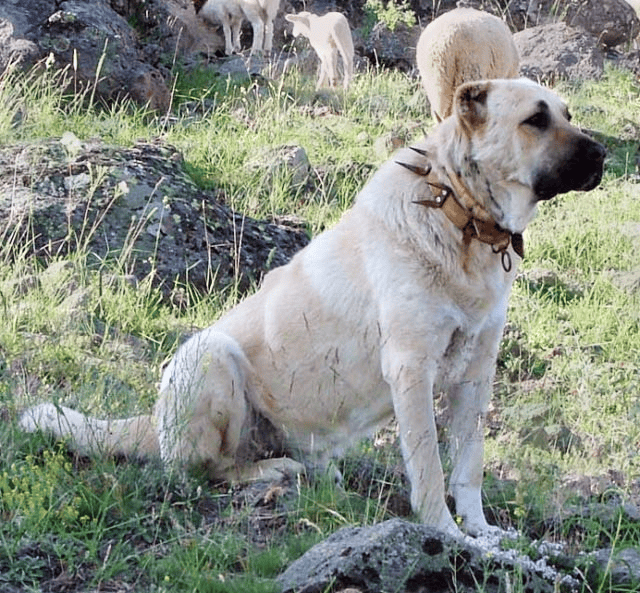

Shortly after our arrival, we were surprised to read of someone who had seen a big cat like a puma or mountain lion late one night in our vicinity. Thereafter we paid special attention to any signs of stalking silhouettes ‒ alas, without any success. I could still recall when British legislation changed in 1976 to make it harder for private owners to keep exotic animals like mountain lions. As a result, many private owners had to take their big cats to vets to be euthanised. Years later, it became apparent that many veterinarians just could not bring themselves to kill the beautiful animals and therefore many were simply released on the quiet. This resulted in many “big cat” incidents, as well as some colourful local legends, such as the ones about the Beast of Bodmin, the Sheppey Panther and the Dartmoor Devil. Between 2010 and 2015, a total of 455 cases were reported to the police by people who were convinced that they had seen big cats. More tangible evidence included the carcasses of sheep with clear marks of claws, as well as leopard DNA identified at the site where a deer had been killed in Devon. Sometimes the paths of people also crossed with these animals, leaving the humans with deep scratch marks. Five domestic cats disappeared in a Cornwall village shortly after traces of a big cat had been noticed and someone even took a cursory video of the scapegoat. All in all, in twenty years the incidents involving “big cats” were quite sporadic and rare though.

Currently, however, there is a widespread return of a much feared native predator happening in many European countries. We all know the story of Red Riding Hood and the sinister wolf who wanted to eat her. Yes, legends and idioms involving wolves, like “a wolf in sheep’s clothing”, or even about werewolves abound. Our European ancestors had a primitive fear of this beautiful predator. In Scotland in 1547, for example, a reward of “sixpence” was promised in return for every wolf killed. Wolves, however, were also admired for their intelligence. The American writer Edward Hoagland, for example, noted that “A mountain with a wolf on it stands a little higher”.

In the European Union, wolves are now protected by law. Their numbers have grown to approximately 12 000. Spain seems to have the largest packs, with an estimated 2 000 to 3 000 animals, Romania and Poland have about 2 500 each, the densely populated Germany has an astonishing 1 300, Greece just more than a thousand, in Italy there are between 600 and 700 (found mostly in the mountainous areas), while in France over 500 of the legendary predators seem to be thriving. Their numbers are growing and their territories are expanding to such a degree that for the first time in a century, during the COVID-19 lockdown, a wolf has been spotted in a village called Londinieres, near the English Channel. Wolves might even be reintroduced to the UK. This could benefit farmers, as scientific reports indicate that the growing wolf population in northern Spain has reduced the incidence of TB among cattle, with wolves keeping the numbers of wild boar and deer in check. The red deer population in Britain has increased dramatically. Deer are involved in about 74 000 collisions with cars annually ‒ in fact, my son-in-law was involved in a crash with a roe deer in Sussex last week, damaging his car. As Ben Macintyre suggests in The Times, “The wolf is at our door, so let’s open it”. The highly successful reintroduction of wolves in Yellowstone National Park ‒ where the biodiversity and vegetation have been enhanced overall due to the wolves changing the migration routes and grazing patterns of the antelope ‒ has opened many people’s eyes to the potential benefits of such projects.

Wild boar, which are quite similar to the South African bush pig, are so common that they have come to be regarded as a pest in large areas of Europe. Cities such as Barcelona, Rome and Berlin are even resorting to special measures to control them, as they raid waste bins in search of garbage and junk food. They can spread diseases such as tuberculosis, hepatitis E and influenza A. The boars may also be infected with so-called African swine fever (ASF), a contagious disease that affects domestic pigs. Barcelona in particular has been affected by this plague of boars that devour garbage, attack dogs and other pets, and cause collisions with vehicles. A tragic accident occurred in 2013, when a policeman tried to shoot a boar and unfortunately wounded his colleague. Teams of veterinarians now do research on where the boars occur and what they are eating. Ways in which the number of productive female boars may be reduced, are also being investigated. In Berlin, “city hunters” have been appointed to systematically work their ways through suburbs where boars are found in order to keep their numbers in check. Still, it is estimated that approximately 3 000 boar are still left roaming the city’s parks and gardens. In Rome, the situation became particularly chaotic when the refuse collectors went on strike. At least half a million boar are shot by hunters in France annually, but even so, farmers continue to complain about crops being destroyed and livestock being eaten. The hunting season is now going to be extended to include the summer months. Wild boar living in cities grow larger and fatter than those living in their natural environment, but their life expectancy is also lower, due to the negative impact of the junk food they eat.

The wild boar is the most commonly occurring mammal in the world. It is found on every continent, except Antarctica. They are intelligent, with a highly developed sense of smell. Boars are fast on land and strong swimmers in water, alert and aggressive when cornered, and extremely adaptable. They eat anything that people eat, but also much more, including carrots, tubers, eggs, salamanders and even lambs, turkeys and calves.

In the United States, boars have been crossbred with domestic pigs. The offspring are known as “wild hogs” and there are about 4 to 5 million of them. This gave rise to the “Hogzilla” phenomenon, a giant wild hog weighing almost 380 kilograms, with tusks respectively measuring 71 and 48 centimetres. This boar was shot by Chris Griffen in Georgia. Originally it was reported to have weighed 450 kilograms, but forensic scientists later exhumed it to weigh and measure it for a National Geographic documentary programme and it was found to weigh closer to 380 kilograms. In 1982, wild hogs were found in 18 US states only. By 2004, their spread had increased to 28 states, while by now, another 3 states have been added. In Georgia, a notorious giant hog named Bear killed 15 trained hunting dogs in his lifetime. Experienced hunters are convinced that the hogs are smarter than dogs.

In Russia, a massive wild boar named King Kong Hog was shot in Ussuriland in 2019, allegedly weighing 535 kilograms, with a shoulder height of 1,58 metres. His weight has not been confirmed by independent sources, but it is obvious that this was a giant animal.

In Australia, wild boars now outnumber humans ‒ there are more than 23 million of them. Hunters targeting them are known as “grunter hunters”. These boars are descendants of domestic pigs originally introduced by Captain Cook.

In Japanese culture, the wild boar is proverbially seen as a dreaded and reckless animal, and numerous idioms include references to it.

When we return to Leeupoort in Limpopo, where we still have a home, the Bushveld’s bush pigs will even eat the skins of pineapples that we throw out to them at night. They are able to crush big bones with a crackle and gnash, almost sounding like hyenas. Who could ever have imagined that the shy, nocturnal bush pig that many people in South Africa confuse with the more conspicuous warthog, is about to take over the world?